How SALR particle clustering works

The Theory

How the particles are modeled

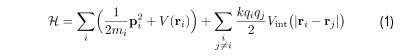

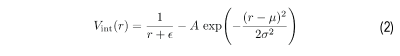

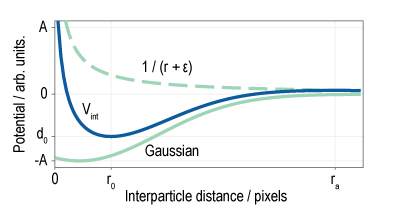

A set of N interacting charge particles can be described by the Hamiltonian (1), where m, p, r, and q represent the mass, momentum, position, and charge of a particle, and |ri - rj| is the distance between ri and rj. V is the confining potential, and Vint is the short-range attractive long-range repulsive (SALR) interaction potential created with a Gaussian attractive term and a 1/r repulsive term, given by (2). An example of what this potential looks like is shown in the figure. The values A, µ, and σ in (2) are set implicitly by giving the potential depth, do; the location of the potential minimum, ro; and the location at which the potential switches from being attractive to repulsive, referred to as the attractive extent, ra.

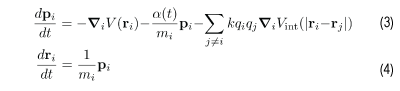

The equations actually describing the motion of the particles can be found from the Hamiltonian, and are given by (3) and (4). And extra term has been added to (3), -α(t) / mi · pi, that does not come from the Hamiltonian; this term slows the particles down over time so that they eventually come to a stop.

Equations (3) and (4) give a set of 2N differential equations that are modeled until the solution converges. The solution is said to converge when the average particle speed over the last few solution steps is below a pre-defined threshold.

How, why, and when SALR clustering works?

The answer comes by analyzing the force on the particles in the simulation: the confining potential puts a force on the particles with a magnitude of |∇V| (which is the slope of the confining potential, like a ball rolling down a hill), and the particles repel each other with a force of about ra-2. If the force from the confining potential is much larger than the repulsive force, |∇V|≫ra-2, then the particles will only find the local minimum of the confining potential—this is what most/all other methods do in finding the local extrema of a voting landscape or finding the local maxima of the point density (mean-shift1). Alternatively, if the repulsive force is much larger than the confining force, ra-2≫|∇V|, then the particles will ignore the confining potential minima and spread out as far apart from each other as possible—this will result is clusters of particles, separated by at least a distance ra, that uniformly cover the region. In between these two regimes, when the two forces are approximately the same order of magnitude, |∇V|~ra-2, there is an interaction between the confining potential and the particle repulsion, and this is the regime that leads to SALR clustering’s improved performance. J. Kapaldo et al., (submitted)2

For additional details, please consult the publication 2

D. Comaniciu and P. Meer, IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 24, 603 (2002). ↩

J. Kapaldo, X. Han, and D. Mary, (submitted) ↩ ↩2